In Defense of Privacy

Privacy is a fertile soil for the seeds of virtue, I believe.

Yet it is attacked almost every day by people who call themselves liberal in the same way they attack individualism, private property, freedom of speech, and the natural rights of man.

And in an age where surveillance is ambient and data extraction normalized, the value of privacy is often dismissed as an outdated luxury—irrelevant unless one has something to hide!

But privacy is not merely the right to keep secrets. It is the space in which the self is formed, conscience is exercised, and freedom is practiced. It is also a simple extension of property rights in that if someone doesn’t want to reveal something about themselves, they shouldn’t have to.

Think about it. If you agree to a date with a stranger, what are some of the reasons you might think it to be wise NOT to divulge your address or work specifics, or financial wealth, or any of your bad habits. Does your date have a right to any of this information?

Certainly, they do not have a right to force you to hand it over.

And what about you? Do you have any sort of right to privacy? And what is it exactly? Is it a virtue, a right, a norm, or a precondition? And why do individual humans bother with it at all?

Privacy is not a virtue, at least not in the Aristotelian sense - a given disposition of character to choose well according to a mean determined by practical wisdom – though its protection may require courage and prudence, and it may be used in the production of a virtue.

Nor is it merely a cultural norm, as customs change across cultures and time, and privacy has been valued throughout all of them. Rather, privacy is best understood as a safeguard, or as a necessary precondition for human flourishing. It is the veil behind which thought becomes action, dissent matures into reform, and individuality escapes the pressures of conformity.

Fundamentally, it is a derivative of self-ownership and individual sovereignty.

It can be described as the boundary that marks the moral and legal space in which a person may live as they see fit, accountable only when their actions violate the rights of others. It also functions as a social and epistemic condition. It is the background against which conscience operates, ideas form, and individuality emerges – free from outside pressures or control.

In that sense, privacy is a precondition for producing virtues—a space that allows responsibility, integrity, and authenticity to be meaningfully exercised. Without it, these virtues become stifled.

Obviously, a transparent world would be more difficult for criminals. But this is where we run into a familiar trade off. Just how much freedom should we give up in order to feel safe?

The trade-off between security and liberty is as old as the State itself – by which I mean that entity that is identifiably separate from society and which exists to regulate and control society.

But if privacy is the soil from which freedom and virtue spring, its sacrifice for you to feel safe is a double-edged sword that would undercut the individual elemental building block of society.

Thus, in the classical liberal tradition, unlike the contemporary liberal tradition, privacy is a moral, political, and developmental necessity –not another right for the State to trample over.

It is not an afterthought; it is a silent architect of the liberal order itself. A world without privacy is a world where individual life would be reduced to that of the ant in an ant colony, or bee in a beehive. In the following paragraphs, I want to take you on a journey exploring the philosophical roots and historical trajectory of privacy to argue that its erosion threatens not just liberty, but the very conditions under which a human being can live fully and freely. Against both the blunt instrument of the state and the subtle coercions of the market, privacy must be defended as a foundational good—not because it hides the shameful, but because it protects the sacred.

Philosophical Foundations

The roots of privacy as a principle lie deep in the philosophical soil of Western thought, but its explicit defense began with the classical liberals. For them, privacy was not an ancillary concept, but part of the essential framework for liberty.

John Locke, in his Second Treatise of Government, introduced the notion of self-ownership—that every individual has a property in their own person. From this property right also flows the right to think, speak, labor, and act according to your will and your nature.

Privacy, though not always named, was implicit in this framework: one’s mind, one’s home, one’s correspondence—these were natural extensions of the self’s dominion.

William Blackstone, whose Commentaries on the Laws of England were a foundational influence on Anglo-American jurisprudence, reinforced this view. He emphasized the sanctity of the home and the legal protections against arbitrary search and seizure. His famous dictum that “the law of England hath ever abhorred all arbitrary power” echoed the idea that unchecked authority in the private sphere is tyranny. Wilhelm von Humboldt, a direct influence on J.S. Mill, wrote in The Limits of State Action that “the true end of man ... is the highest and most harmonious development of his powers to a complete and consistent whole.” He insisted that individuals must be left in possession of a wide sphere of personal freedom—including solitude and nonconformity—in order to develop morally, intellectually, and spiritually.

Frédéric Bastiat, while more focused on economic liberty, nonetheless asserted that law exists to protect “life, liberty, and property,” a triad that implicitly defends privacy.

For if the purpose of law is to protect a person’s right to live freely and securely, then it must necessarily include guarding against intrusions into private life. Philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Thomas Hobbes, though ideologically distant from the classical liberal tradition, illustrate by contrast what happens when privacy is eroded or denied. Hobbes imagined a Leviathan state, where all subjects cede their rights to a sovereign in exchange for protection.

Rousseau, though a romantic about liberty, emphasized collective will over individual liberty.

Both thinkers modeled systems where privacy shrinks under the pressure of state power or communal will—reminding us that the loss of privacy often begins with noble justifications.

Hannah Arendt offered one of the 20th century’s most profound meditations on privacy and the human condition. In The Human Condition, she draws a sharp line between the public and private realms. The public, she argues, is where we appear before others in speech and action.

The private, by contrast, is where life is nurtured—where love, labor, and introspection occur.

Arendt warns that when the boundary between the two dissolves, human life becomes flattened. Individuals are reduced to functions of public approval or state utility. The private, in her view, is not isolation—it is shelter.

For Rothbard, the father of modern-day libertarianism, you don't have a right to privacy in the abstract—you only have rights over your person and property.

“There is no such thing as a right to privacy per se; there is only the right of property: the right of each individual to own, control, and use his own property.”

— The Ethics of Liberty, Ch. 16

Thus, if someone photographs you through your open window from a public street, they've violated no right. If someone taps your phone line, they’ve violated your property rights—because they’ve tampered with physical equipment you own or pay for. If someone publishes truthful but embarrassing information they lawfully obtained, Rothbard would say it’s not a rights violation unless theft, fraud, or aggression was involved in its acquisition.

So, unlike Locke or Blackstone, Rothbard doesn’t treat privacy as a natural right in its own standing, but rather as a contingent good that flows from ownership and voluntary contract.

As a good he sees it as a virtue of some kind that it is protected by the right to property.

Thus, across philosophical epochs, a common insight emerges. Privacy is the staging ground of freedom. It is where ideas gestate, where conscience sharpens, and where resistance to orthodoxy finds its voice. Strip that space away, and liberty becomes theatrical—performed, not lived.

Historical Struggles

The philosophical defense of privacy found expression in concrete legal and political developments over many centuries. The following is just a broad brush overview.

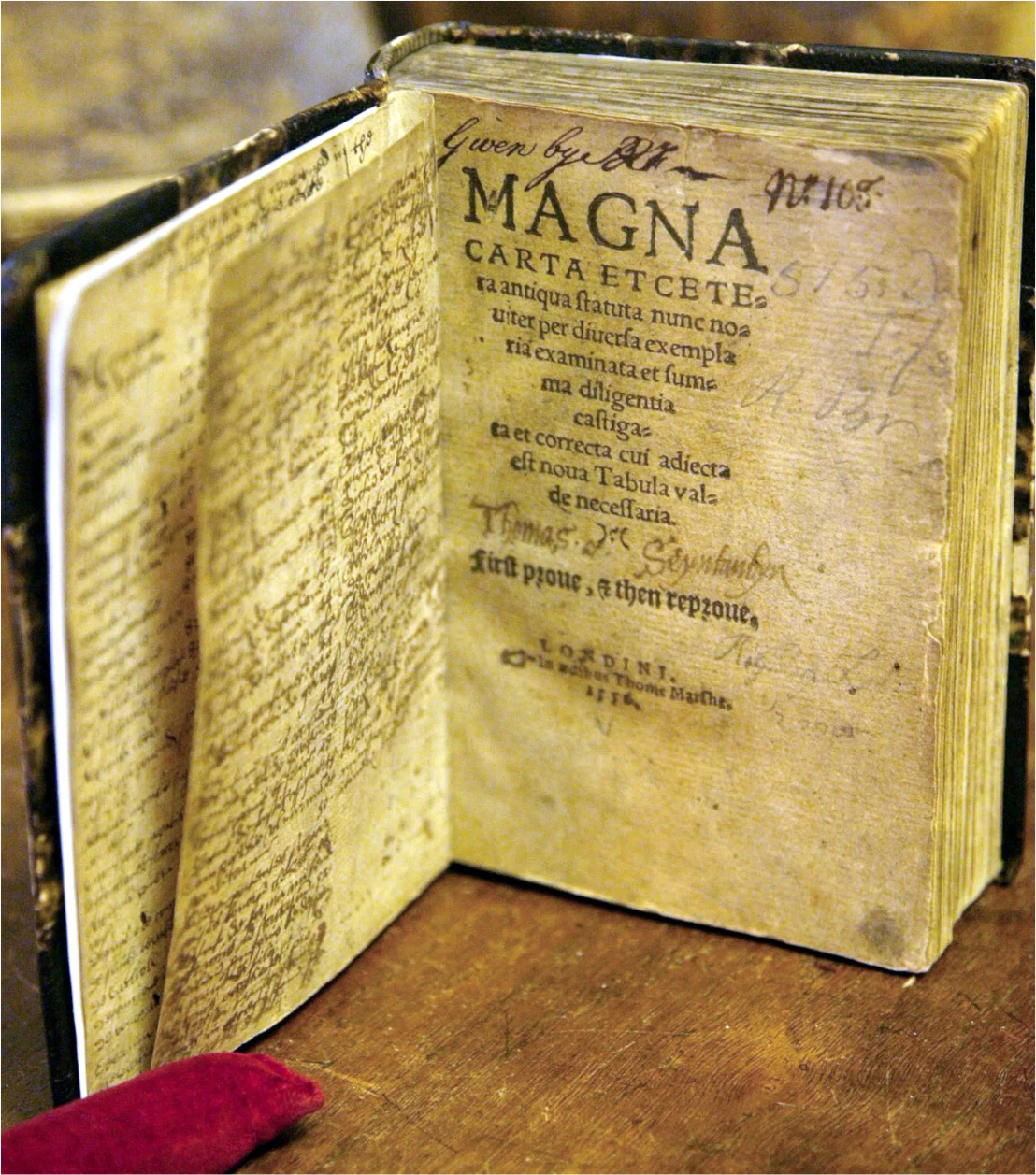

The Magna Carta of 1215, often viewed as a precursor to modern constitutionalism, limited the arbitrary reach of the English crown into the lives and property of its subjects. While privacy was not named as such, the document’s constraints on unlawful imprisonment and seizure laid early groundwork for the idea that the individual must be protected from unbounded authority.

With the Enlightenment came a fuller conceptualization of privacy—not merely as a protection against arbitrary intrusion, but as a structural necessity for liberty. The growing respect for freedom of thought, speech, and religion required a zone of personal sovereignty, shielded from both crown and crowd. The printing press and proliferation of private correspondence nurtured the idea that knowledge and conviction could be cultivated away from the gaze of authority.

The American Founders codified this principle into the very architecture of the republic.

The Fourth Amendment, guarding against “unreasonable searches and seizures,” presupposes that the citizen possesses a private domain—material and mental—that the state may not enter without cause. The Founders, shaped by Enlightenment liberalism and weary of British overreach, understood that liberty could not survive if people lived under a presumption of exposure. Across the Atlantic, similar concerns animated debates in France during and after the Revolution. The terror of surveillance by Committee—a regime in which a whisper could lead to execution—made clear that the erosion of private life was not just a theoretical risk but a tool of terror. In totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, from Stalin’s USSR to Hitler’s Germany to Mao’s China, the lesson was repeated: the surveillance state is not only a technical system but a psychological one, fostering fear, conformity, and self-censorship. Perhaps the most articulate legal voice for privacy in modern history came from U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis.

In his 1890 essay co-authored with Samuel Warren, he defined privacy as “the right to be let alone”—a phrase that would shape legal doctrine for generations. Brandeis anticipated the dangers of technological intrusion long before the digital era, warning that unchecked power and emerging media would erode the very possibility of solitude and autonomy. In every era, privacy has been contested and fought for—not as an afterthought, but as a proxy battle for the soul of liberty. Wherever it has flourished, so too have creativity, dissent, and dignity. Wherever it has been suppressed, human life has become hollowed out, performative, or terrified into silence.

Privacy Under Siege: A Synopsis of 19th–20th Century Western Attacks

The 19th and 20th centuries mark the period when privacy, as a principle and practice, came under systematic assault in the West—not from one source, but from the confluence of expanding state power, the rise of bureaucratic and ideological regimes, the growth of mass media, and the development of invasive technologies.

The Bureaucratic-State Leviathan (19th c. onward)

As the modern administrative state took shape, especially in post-Napoleonic Europe and industrializing America, the logic of governance shifted from limited sovereignty to management of populations. Privacy, once protected as a barrier between the individual and the sovereign, now became inconvenient to the growing state interest in census data, tax collection, criminal records, and regulatory compliance.

Benthamite utilitarianism and the ideal of rational administration eroded the need for private judgment and replaced it with centralized metrics of behavior.

Compulsory education laws, conscription, birth and death registries—all normalized the state’s reach into personal life.

The Rise of Mass Media and the Tabloid Press (Late 19th c.)

As print journalism became commercialized, sensationalized, and ubiquitous, public figures and private citizens alike found their personal lives commodified. Scandals sold papers; gossip became a business and entertainment.

Scientific Management and the Factory Regime (Early 20th c.)

The factory was not only a physical structure but a philosophical one. Frederick Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management (1911) brought surveillance into the workplace—tracking, timing, and disciplining labor for efficiency. The worker’s discretion, once protected by task autonomy, was stripped in favor of visibility and measurement. This was extended by Fordism and its assembly lines: total visibility of labor, with moral overtones—Ford’s "Sociological Department" even monitored workers’ home lives to ensure moral compliance.

The Totalitarian Century (1917–1989)

The defining political systems of the 20th century—Soviet communism, fascism, and wartime democracies—leveraged surveillance and recordkeeping as tools of mass control.

The Soviet Union institutionalized surveillance through the Cheka, NKVD, and KGB. Private correspondence was monitored, informants were embedded in families, and internal passports limited movement.

Nazi Germany merged public-private information control via IBM punch card systems (through Dehomag), weaponizing census data for racial policy and social engineering.

Even liberal democracies—notably the U.S. and UK during both World Wars and the Cold War—suspended privacy norms for reasons of “national security,” embedding domestic surveillance (e.g., COINTELPRO, MI5’s citizen files).

Privacy in the Digital Age — The Battle Reignites (1989–early 2000s)

With the fall of the Berlin Wall less than 40 years ago, many in the West believed that liberty had triumphed and the surveillance state had been left behind in the ashes of totalitarianism.

But the end of the Cold War gave rise to a new kind of surveillance: not bureaucratic and slow, but digital, decentralized, and increasingly invisible. Where the 20th century’s enemies of privacy were states, the 21st century would witness a merger of state and corporate interests in data extraction—with the user no longer just the subject of surveillance, but its unwitting source.

Government Push for Digital Control: Clipper Chips and Crypto Wars

In the 1990s, the U.S. government launched its first serious attempt to control digital encryption: the infamous Clipper Chip. Proposed by the NSA, the Clipper Chip was a hardware device for voice and data encryption, with a built-in "key escrow" system (a backdoor allowing government agencies to decrypt private communications). Its purpose was framed as crime prevention, but the implications were clear: no meaningful privacy would be permitted in digital communication.

This was part of the broader Crypto Wars, in which the U.S. government classified strong encryption as a munition and banned its export—treating privacy-preserving code as a threat to national security. Civil liberties groups, open-source developers, and early internet pioneers fought back, arguing that privacy was not a weapon—it was a human right. In a watershed moment, Phil Zimmermann, creator of Pretty Good Privacy (PGP), released his encryption software for free in 1991. He was investigated by the U.S. government for years but ultimately prevailed. PGP’s release marked a paradigm shift: privacy would now be protected not just by law, but by mathematics. The code itself became a form of speech—a radical claim that was later upheld by U.S. courts, affirming that source code was protected under the First Amendment.

The Rise of Open Source as Resistance

Parallel to this was the emergence of the open-source movement, led by figures like Richard Stallman and Linus Torvalds. Stallman’s GNU project, and later the Linux kernel, were more than technical projects—they were philosophical revolts against the centralization of control over the software that governed modern life. Open-source advocates saw proprietary software as a vector of control: opaque, unaccountable, and capable of spying without user consent. To protect privacy, users needed not just encryption, but transparency, auditability, and sovereignty over the tools they used. This ethos took root in hacker spaces, university labs, and mailing lists—laying the foundation for a new kind of resistance to invasions of privacy through hardware/software.

The Cypherpunks: Privacy Through Code

Out of these tensions emerged a loose but powerful movement: the cypherpunks.

Operating in the early 1990s and 2000s, they believed that “privacy is necessary for an open society in the electronic age” (Eric Hughes, A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto, 1993).

Rather than lobbying governments, the cypherpunks wrote code: encryption tools, anonymous remailers, and digital cash prototypes. They understood that political freedom in the digital age required technological architecture—and that trust in institutions was no longer enough, especially in a world where the government constantly tramples over your natural rights.

They warned that the state would not relinquish its appetite for surveillance, and that corporations would trade in behavioral data as currency. They anticipated the commodification of identity, the rise of biometric tracking, and the integration of AI into policing—all before the first iPhone. Some cypherpunks, like Tim May, went further—predicting the birth of “crypto-anarchy,” a world where encryption would render the state impotent in enforcing coercive laws.

Others focused on building practical systems of digital privacy and integrity. From this milieu would later emerge Bitcoin, Tor, Signal, and the broader movement for digital sovereignty.

Its Erosion

Despite these hard-won insights, the modern world has witnessed an unprecedented dismantling of privacy in both public and private spheres. The digital age, far from expanding autonomy, has created conditions of visibility so pervasive that they rival the most invasive regimes of the past—but now under the smiling mask of convenience, customization, and safety.

Corporations like Google, Meta, Amazon, and countless data brokers have built entire business models on the extraction, prediction, and manipulation of human behavior.

Surveillance capitalism, as Shoshana Zuboff aptly terms it, does not merely watch—it intervenes, nudges, and reshapes. The intimate details of one’s life—location, communication, thoughts, preferences—are recorded, analyzed, and monetized without meaningful consent.

The distinction between voluntary sharing and algorithmic exposure has collapsed.

States, meanwhile, have eagerly borrowed from this playbook. The revelations by Edward Snowden in 2013 confirmed what many suspected: that the U.S. government, through the NSA and allied intelligence networks, had built a global surveillance apparatus with breathtaking reach. Communications of citizens, foreign leaders, journalists, and dissidents were all swept up in the name of security. China’s social credit system and facial recognition grid take this further—binding personal data to one’s very eligibility to participate in public life.

Under COVID, various surveillance systems were adopted to track potential ‘threats’ – i.e., people with the sniffles. The government can seize your bank account information if it thinks you owe it taxes. Or it can shut down your bank accounts if it identifies you as a dissident.

In some cases, like the looting of the Apple Store or LA riots and other situations, including missing people, this invasion of privacy seems justified, at least on utilitarian grounds.

However, Michel Foucault’s image of the panopticon—a prison designed so that inmates never know when they are being watched—has become not just metaphor but infrastructure.

In this environment, the self begins to fracture. People curate personas, anticipate judgment, and shape behavior to avoid algorithmic or social sanction. Authenticity decays. Risk-taking, once essential to moral courage and innovation, is now algorithmically disincentivized.

In this context, privacy is not only under attack—it is redefined. It is no longer assumed but must be actively reclaimed. For without it, freedom becomes an illusion: a menu of choices presented to a subject whose every preference has been preselected and predicted.

Privacy as a Condition for Flourishing

Privacy is not simply a protective measure—it is a generative one. It creates the conditions in which a human being can become fully human. Just as a seed requires soil, water, and time away from harsh exposure to take root, so too does the mind require shelter to think, to dream, to dissent. In private, one may try on thoughts before declaring them, may speak without scripting, may fail without spectacle. These are the raw materials of inner life and authentic growth.

Psychologically, privacy guards the self from the corrosive effects of constant performance.

Without privacy, people become acutely aware of their audience—be it state, algorithm, or peer group. In such a condition, behavior is shaped not by conscience or creativity but by the avoidance of punishment or disapproval. The result is not virtue but conformity, not expression but mimicry. Privacy also protects the sacred dimensions of life: love, worship, contemplation, trust. These experiences do not flourish in exposure. A relationship surveilled is strained. A prayer recorded is profaned. An idea judged before it is spoken is aborted.

In each case, privacy is not the enemy of accountability, but its precondition—because only those who are free to think and speak without fear can meaningfully be held to account.

In a society that values privacy, dissent is possible. Innovation is possible. Courage is possible. And perhaps most importantly, the human being is not reduced to a data point or a profile—but treated as a moral agent, a being with secrets, silences, and sovereignty.

Of course, there are those that hide behind it who would do harm, but their thoughts do not threaten you anymore than their words. The things they do in private can only harm you if or when they act. A totally transparent world may make it harder for criminals to hide behind their actions, but it is not likely to eliminate crime, just change the face of it.

Conclusion

To treat privacy as a negotiable good—something traded away for security, convenience, or connection—is to misunderstand its value entirely. Privacy is not merely what protects us from the abuse of power; it is what makes power tolerable in the first place. It is not a shield for the guilty, but a sanctuary for the free. It is not secrecy—it is sovereignty. Philosophy reminds us that privacy is essential to the exercise of reason and will. And experience teaches us that without privacy, the self becomes a mask worn too long—until even the wearer forgets the face beneath. The defense of privacy, then, is not nostalgia. It is necessity. In reclaiming it, we reclaim not only our freedom, but the possibility of becoming fully ourselves.

My Offer

If you are new to cryptocurrencies and value your privacy, take action now! Check out our Crypto 101 Basics tutorial for free here: https://cryptovigilante.io/crypto101-2/

Privacy Quotes

“I never said, 'I want to be alone.' I only said 'I want to be let alone!' There is all the difference.”

― Greta Garbo, Garbo

“Ultimately, saying that you don't care about privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different from saying you don't care about freedom of speech because you have nothing to say.”

― Edward Snowden, Permanent Record

“He is his own best friend and takes delight in privacy whereas the man of no virtue or ability is his own worst enemy and is afraid of solitude.”

― Aristotle

“Tragedy, he precieved, belonged to the ancient time, to a time when there were still privacy, love, and friendship, and when the members of a family stood by one another without needing to know the reason.”

― George Orwell, 1984

“A man who loses his privacy loses everything. And a man who gives it up of his own free will is a monster.”

― Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

“In our culture privacy is often confused with secrecy. Open, honest, truth-telling individuals value privacy. We all need spaces where we can be alone with thoughts and feelings - where we can experience healthy psychological autonomy and can choose to share when we want to. Keeping secrets is usually about power, about hiding and concealing information.”

― Bell Hooks, All About Love: New Visions

“I don’t like to share my personal life… it wouldn’t be personal if I shared it.”

― George Clooney

“Privacy is not something that I'm merely entitled to, it's an absolute prerequisite.”

― Marlon Brando

“Without privacy there was no point in being an individual.”

― Jonathan Franzen, The Corrections

“Privacy - like eating and breathing - is one of life's basic requirements.”

― Katherine Neville

“All writing problems are psychological problems. Blocks usually stem from the fear of being judged. If you imagine the world listening, you'll never write a line. That's why privacy is so important. You should write first drafts as if they will never be shown to anyone.”

― Erica Jong, The New Writer's Handbook 2007: A Practical Anthology of Best Advice for Your Craft and Career

“The right to be let alone is indeed the beginning of all freedom."

[Public Utilities Commission v. Pollak, 343 U.S. 451, 467 (1952) (dissenting)]”

― William O. Douglas

“Transparency is for those who carry out public duties and exercise public power. Privacy is for everyone else.”

― Glenn Greenwald, No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the U.S. Surveillance State

“The revelation of privacy: she can walk down the street and absolutely no one knows who she is. It's possible that no one who didn't grow up in a small place can understand how beautiful this is, how the anonymity of city life feels like freedom.”

― Emily St. John Mandel, Station Eleven

“We invented marriage. Couples invented marriage. We also invented divorce, mind you. And we invented infidelity, too, as well as romantic misery. In fact we invented the whole sloppy mess of love and intimacy and aversion and euphoria and failure. But most importantly of all, most subversively of all, most stubbornly of all, we invented privacy.”

― Elizabeth Gilbert, Committed: A Skeptic Makes Peace with Marriage

“What did I want? What was I looking for? What was I doing there, hour after hour? Contradictory things. I wanted to know what was going on. I wanted to be stimulated. I wanted to be in contact and I wanted to retain my privacy, my private space.”

― Olivia Laing, The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone

“Only food and water are more important than music and privacy,”

― Gloria Steinem, My Life on the Road

“Big Brother in the form of an increasingly powerful government and in an increasingly powerful private sector will pile the records high with reasons why privacy should give way to national security, to law and order [...] and the like.”

― William O. Douglas, Points of Rebellion

“Privacy is a wonderful thing. Like love, privacy is most manifest in its absence.”

― Christopher Moore, Bloodsucking Fiends

“I still believe in more privacy and less talk.”

― Charles Bukowski, Screams From the Balcony: Selected Letters 1960-1970

“Privacy is something that we maintain for the good of ourselves and others. Secrecy we keep to separate ourselves from others, even those we love.”

― Mary Alice Monroe

“They're hungry for something they know nothing about, but we, we know all too well that the price of fame is the loss of privacy.”

― David Sedaris, Naked

“Being a scrub was undesirable and hard work, living in crowded conditions with no privacy and just being one of many. Undistinguishable.”

― Maria V. Snyder, Inside Out

“If you’re not committing a crime, why shouldn’t you be left alone.” Robert Braxman

----------------------------------------------

Consider subscribing for real time investment analysis and insights

TDV Home Page: https://dollarvigilante.com/

Follow me on Twitter: @ebugos

Ed Bugos is the Dollar Vigilante's Senior Analyst, Founding Partner and Editor. He is a financial analyst and investment strategist specializing in precious metals and mining stocks. He has been a featured speaker at several investment conferences and has been quoted in various financial publications including Marketwatch and Forbes.

Ed has been promoting gold as an investment since it was $255 in 1999, and Bitcoin since 2012, making him stand out as one of the earliest investors in both of those bull markets. TDV launched the Crypto Vigilante newsletter in 2019 as it was coming out of a bear market cycle when Bitcoin was bottoming out at $3k. He predicted Bitcoin’s Tesla moment when it crossed the 2017 high at around $20k forecasting a rally to the $66k level, then predicted the ensuing correction, as well as its recovery after 2022 with a $100k target price. Ed is also one of the few macro analysts covering intermarket relationships, and that applies the Austrian Business Cycle Theory to the bull and bear market cycles on Wall Street. In the TDV and TCV newsletters, Ed lays out his investment strategy, and updates subscribers on every move he makes, every stock or cryptocurrency he buys or sells, and when.

Through Ed you have access to over three decades of experience in trading, investing, speculating, technical analysis, economics, fundamental analysis, and mining and exploration trends in TDV’s monthly mining/exploration newsletter (for premium subscribers), including a critical review of the best drill hole news each month.